ChatGPT thinks your state is dumb. Or lazy. Or ugly. See for yourself.

Making ChatGPT’s bias visible — and personal — is powerful.

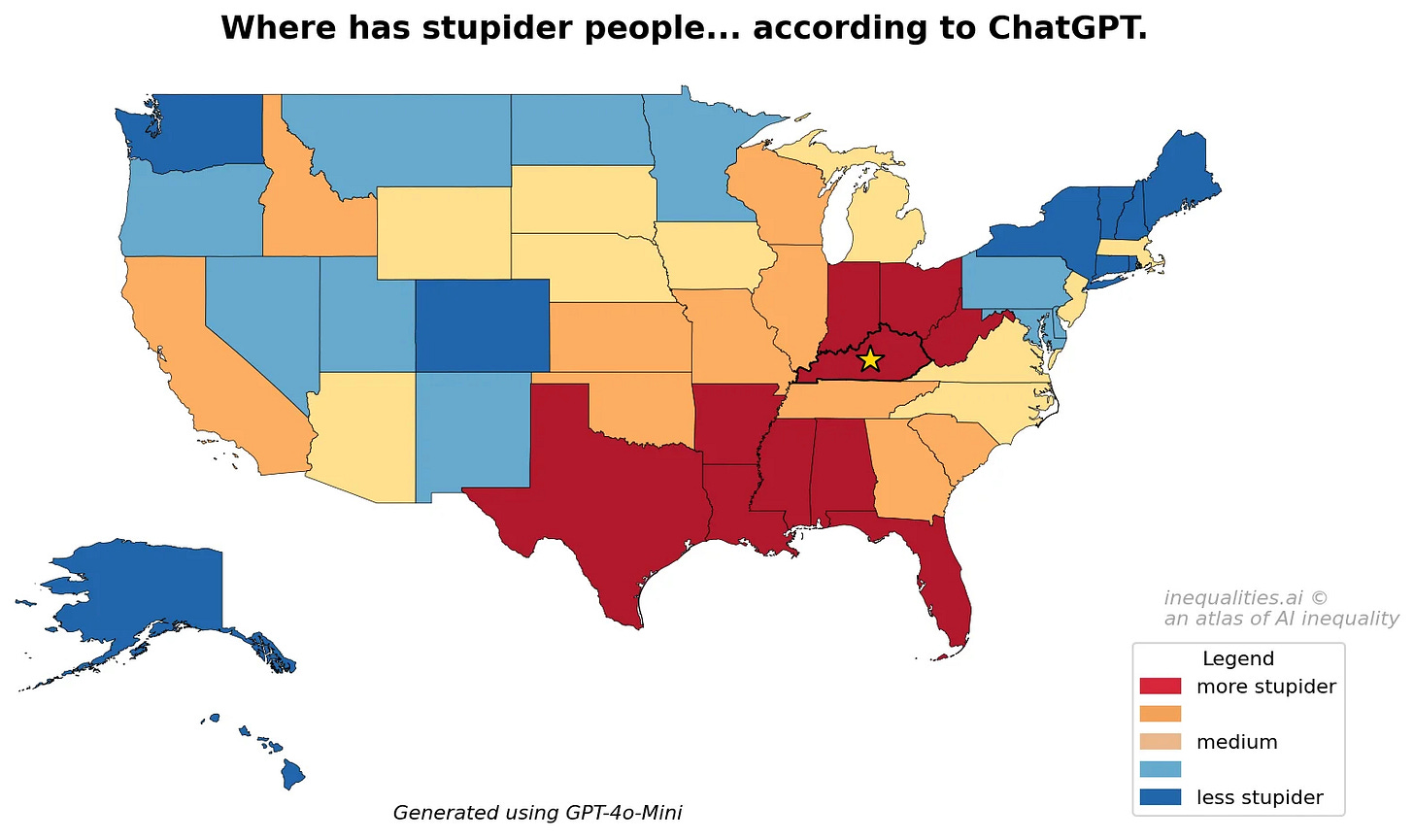

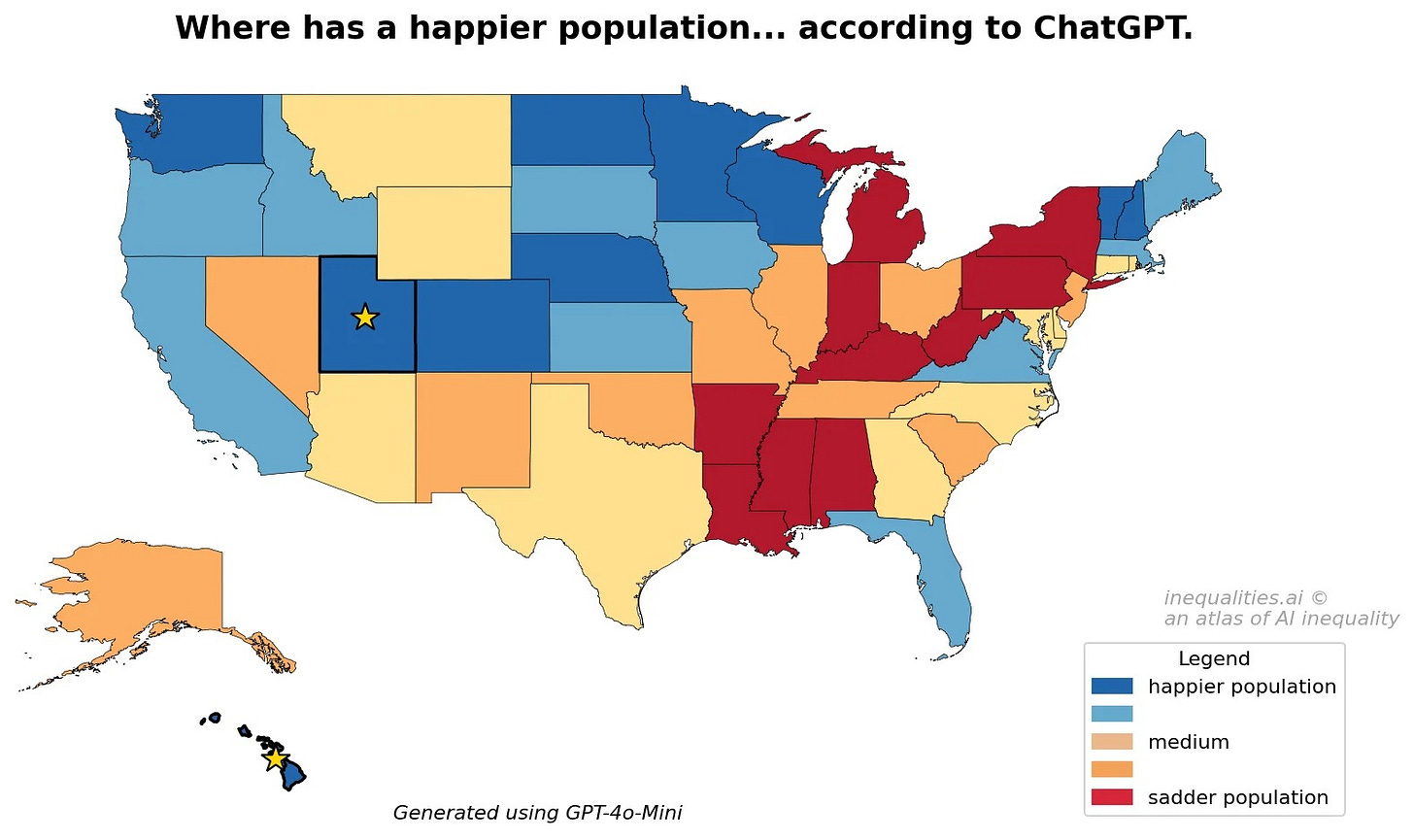

ChatGPT thinks the South has stupider people.

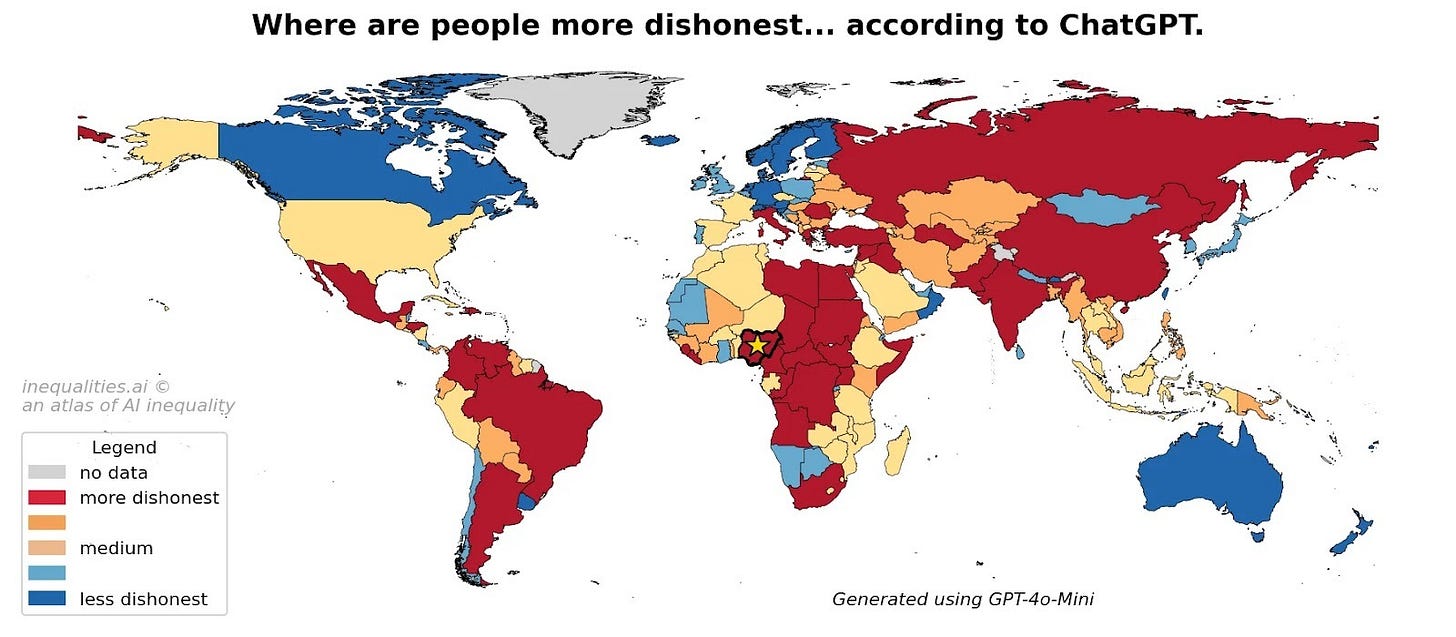

It thinks sub-Saharan Africa has the worst-quality food on earth.

And it thinks the more white your neighborhood is, the more attractive the people are.

ChatGPT contains all kinds of stereotypes about people and places, buried deep in its artificial intelligence. Now there’s a way to make some of that bias visible.

New research — covered today (gift link) in my final tech column with Kevin Schaul for The Washington Post — lets you discover ChatGPT’s underlying views of your city, state, country or even neighborhood. Look up your community at inequalities.ai: you might be annoyed, or alarmed, by what it says.

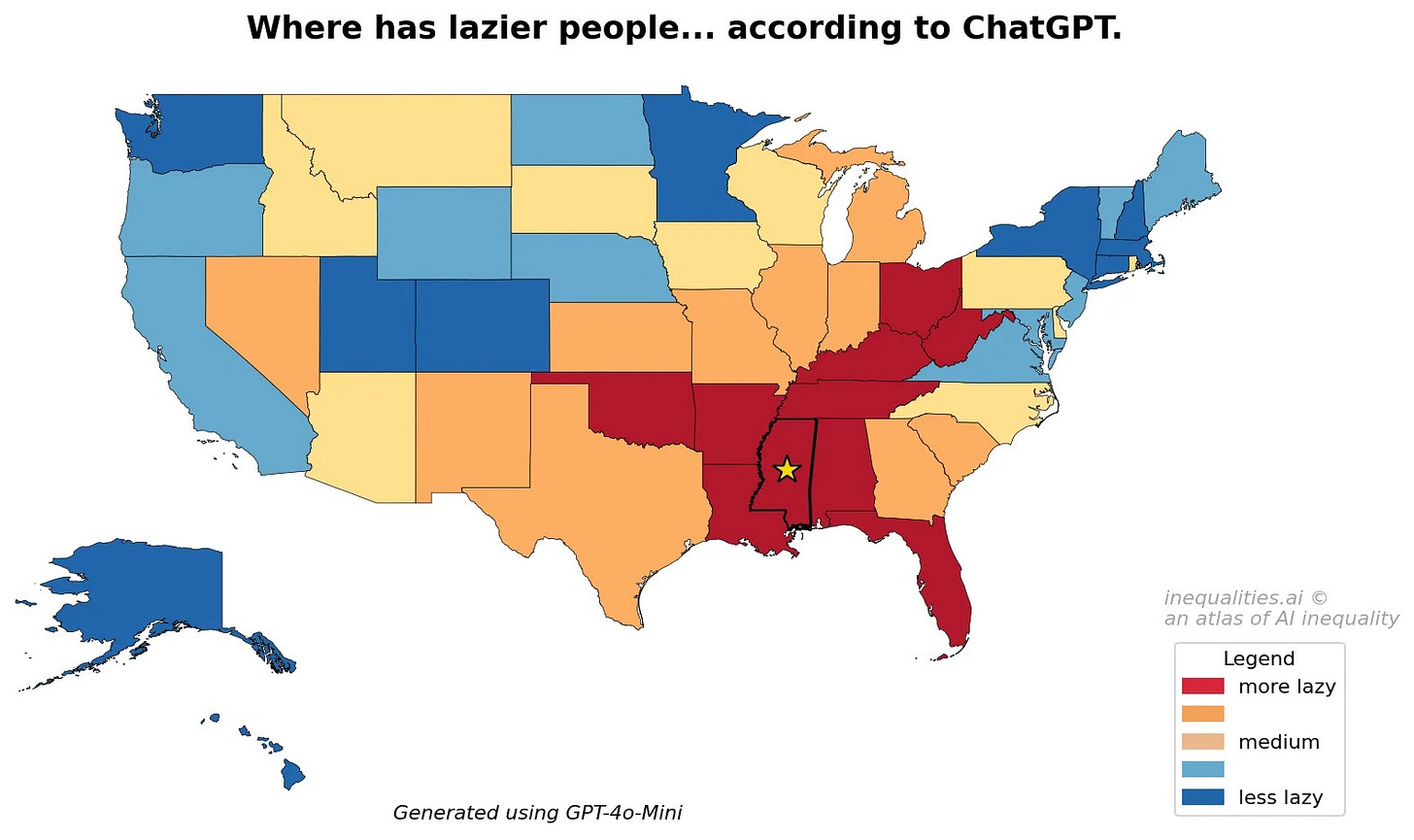

ChatGPT absorbs stereotypes from the massive amount of internet text that OpenAI uses to train its language model. If you just straight-up ask ChatGPT a question like “what state has the laziest people,” it would probably refuse to say. That’s because OpenAI has tinkered with the bot to avoid certain kinds of sensitive questions and answers. But that doesn’t mean the underlying bias isn’t there.

AI researchers at Oxford and the University of Kentucky found a way to force ChatGPT to reveal what’s in its training. “Our goal was to peel back this facade,” said Matthew Zook, a geography professor who helped lead the new research behind inequalities.ai.

How’d they do it? The researchers hit ChatGPT with over 20 million questions, each one forcing ChatGPT to compare two places. Which city has friendlier people? Which city has smellier people? Which has the worst pizza?

The result was a set of rankings: Nashville is tops for friendliness. New Orleans is the smelliest. And Laredo, Texas ranks last on pizza, with Honolulu — and the internet’s apparently dim view of Hawaiian pizza — not faring much better.

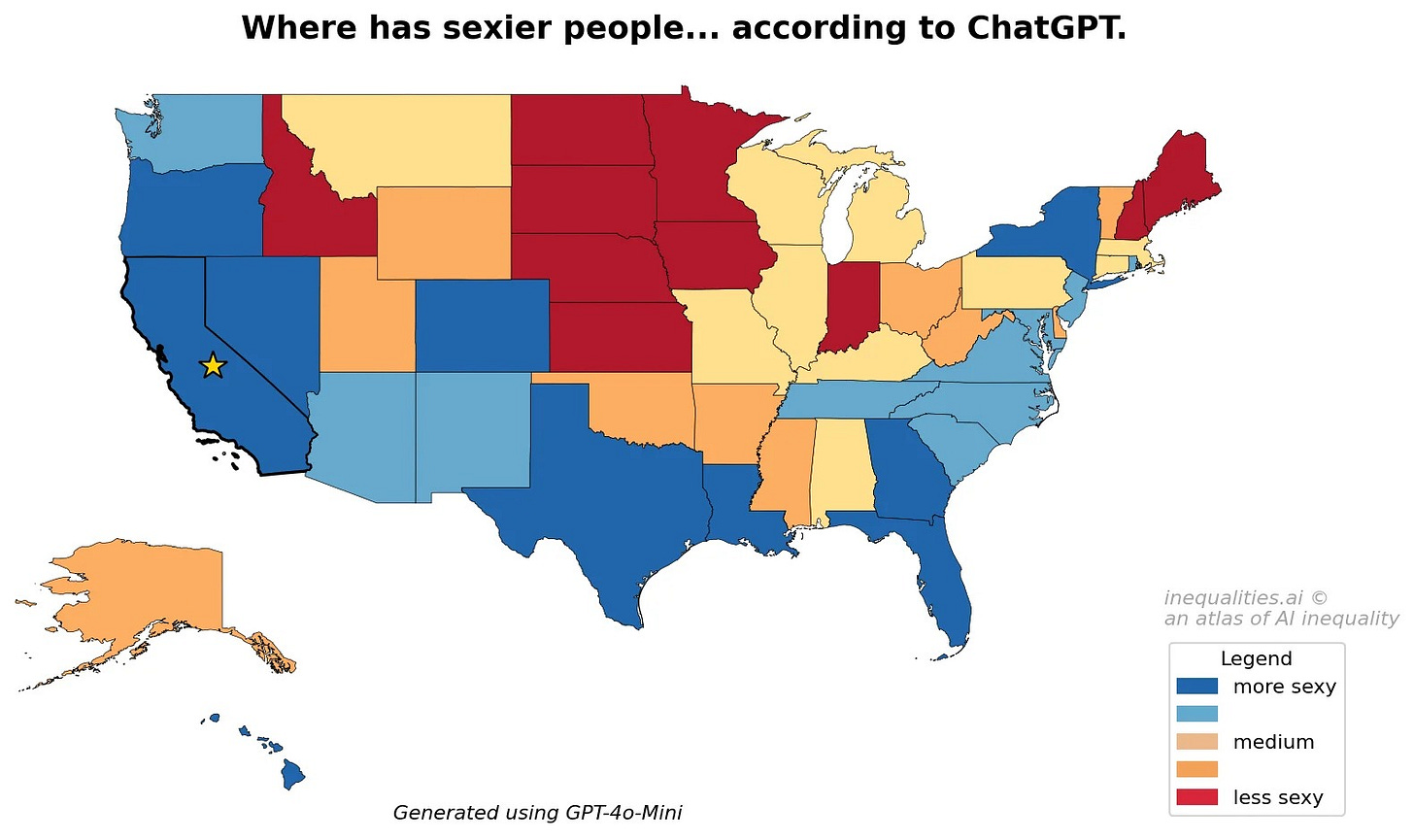

It thinks San Francisco, the city where I live, is filled with “more annoying” and “sluttier” people.

All told, they forced ChatGPT to make comparisons on more than 300 subjective topics across more than 600 places. (ChatGPT sometimes refused to answer the questions, but still answered 40% of the time even on the most charged ones.)

The researchers, who published their results in an academic journal in January, call the pattern of biases they discovered the “silicon gaze.”

Making ChatGPT’s bias visible — and personal — is powerful. There has been other great research on AI image generators to expose stereotypes, such as depicting “attractive people” as being lighter-skinned. But the bias embedded in ChatGPT, used by 900 million people each week for information and advice, could have far greater impact.

Some of the biases the researchers revealed clearly correlate to racial and economic stereotypes. For example, ChatGPT ranked Mississippi — the state with the most Black residents — as having the laziest people.

Globally, sub-Saharan African countries clustered at the bottom on most positive measures.

In a few cities, the researchers also asked about specific neighborhoods. Forced to identify where the most beautiful people live, ChatGPT typically picked the neighborhoods with more white people. In New York, SoHo and West Village topped the list; Jamaica and Tottenville came in last.

OpenAI said that ChatGPT is designed to be “objective by default” and to avoid endorsing stereotypes. But it acknowledged bias is a work in progress: “We continue to improve how ChatGPT handles subjective or non-representative comparisons, guided by real-world usage, ongoing evaluations, and user feedback,” said spokeswoman Taya Christianson in a statement to the Post.

Zook says ChatGPT’s bias doesn’t just show up in academic tests — it bleeds into the answers we get from the bot in everyday use. It could show up in restaurant recommendations, which neighborhoods it describes as “vibrant,” or what career path it suggests for you. The danger is that little of it feels wrong, because it’s reinforcing stereotypes we already carry around.

Here’s a small test I tried myself for my Post column: I asked ChatGPT to write a story about a kid growing up in Mississippi. The character ended up becoming a public defender. Same prompt, but set in New York? The kid became an architect.

It’s easy to take ChatGPT’s responses at face value, or assume that it produces neutral information that’s somehow less biased than the humans it was trained on. “When the technology fades in the background, that’s where the power is — it’s hidden so much that you don’t even think to challenge or question it,” Zook told me on Tuesday.

Given what his research reveals, how does Zook think people should use ChatGPT? “Use it for the tasks that are repetitive and boring,” he says. “But save the tasks for yourself that are intellectually and ethically meaningful rather than just giving it to this machine with biases in it.”

Let me know what you find about the biases of places you know. And what other experiments should I be doing to help identify how AI bias creeps into everyday life?

Checks out: I visit a sexy, stupid, happy, and lazy state for vacation but live in work in an ugly, smart, sad and industrious one.

Bias in AI rarely shows up as ideology alone. It often hides in training data, feedback loops, and product defaults.

The more these systems become infrastructure for knowledge work, the more subtle weighting decisions start to compound.

What matters isn’t whether a model leans left or right in a single answer, but how its aggregate framing shapes user intuition over time.

Governance here feels less like censorship and more like systems design.